Ask The Mind Coach is dedicated to the “mental” part of hockey from both player and parent perspectives. Shawnee Harle takes your questions and provides feedback based on her experiences and training. If you have a question to Ask The Mind Coach, email us!

“It feels like the dream is over for my son who wasn’t taken in his U16 draft. He doesn’t want to quit and is locked in on doing something in hockey at a high level but I don’t think he is good enough once I take my parent goggles off. We have had discussions about focussing on school and perhaps getting a job but he is determined to keep going,. He works harder than most kids but the talent just doesn’t match his effort level. What is the best way to tell my kid that his hockey dream is probably over?”

I suggest letting this play out a bit longer.

If you force him to quit, he may be resentful and blame you for squashing his dream. Some athletes just won’t take NO for an answer and that’s not a bad thing.

It’s really difficult to let go of, or give up on a dream when investment is high.

“Those who invest the most are the last to surrender.”

If there aren’t any major disadvantages or life altering situations that will occur if he continues to chase his dream, let him keep chasing. He has the rest of his life to work. School should be a focus regardless.

In the end, the cream always rises to the top.

Give it more time. At some point it will become obvious to him, one way or the other.

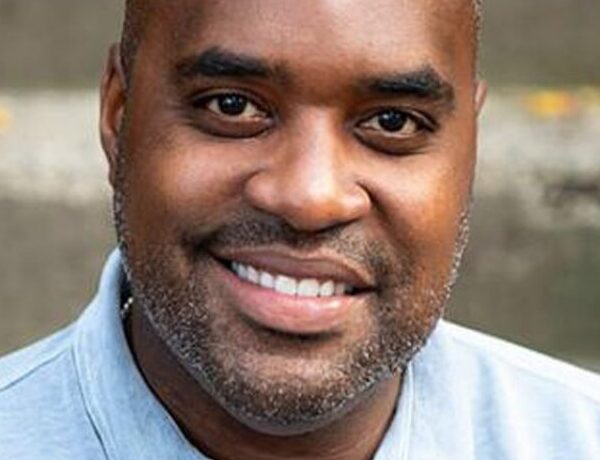

Shawnee is a two-time Olympian with 26 years of elite coaching and leadership experience. She is a Mental Toughness Coach and helps athletes of all ages gain a competitive edge, get selected to their dream team, earn that scholarship, and compete with COURAGE and CONFIDENCE when it matters most. And because it take a village, Shawnee also works with their parents. Learn more at shawneeharle.com

More from The Mind Coach

What if a hockey player just doesn’t give any effort when they are on the ice even though they love playing the game?

Do you or your player suffer from a lack of confidence with the puck despite having obvious skill? The Mind Coach explains why this happens.

What if a hockey player just doesn’t give any effort when they are on the ice even though they love playing the game?

What if a player is reluctant to engage in battles for the puck? How can you coach a player to be more aggressive?

There are all kinds of different “slumps” a goalie can go through including the “Blinks”. The Mind Coach offers a few solutions to try …

The post How Do I Tell My Son His Hockey Dream is Over? appeared first on Elite Level Hockey.

.

.